DNS & BIND - Betrieb und Sicherheit (Linuxhotel)

1 Course Notes and exercises

This page contains the course notes and exercise instructions for attendees of the training DNS & BIND - Betrieb und Sicherheit (Linuxhotel).

Click on images to zoom in.

1.1 Introduction

- What is your interest in DNS & DNSSEC?

- What is your prior knowledge of DNS & DNSSEC?

- What do you want to learn about DNS & DNSSEC?

2 New terminology used in DNS & BIND

- The terms

masterandslavehave been used to describe primary and secondary authoritative DNS servers in the past.- However this terminology is wrong and misleading, for reasons discussed in the Internet Draft Terminology, Power, and Inclusive Language in Internet-Drafts and RFCs: https://tools.ietf.org/html/draft-knodel-terminology

- in this document, and in configuration examples, we are using the

new terms

primary(instead ofmaster) andsecondary(instead ofslave) whenever possible. - BIND 9 has started adopting the new terms with BIND 9.14, however

the transition is not complete, and some terms in configuration

statements still use the old terms. This will change with

future releases

- if you use an older version of BIND 9, please substitute the new terms for the older ones

- the old terminology will also be found in older books and standards documents (RFCs and Internet Drafts)

- DNS terminology can be confusing and is sometimes overloaded. RFC 9499 DNS terminology ( https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc9499 ) tries to collect and document the current usage of DNS terminology.

3 Building the authoritative DNS server

- Repeat the steps for the next chapter on the

nsNNNaandnsNNNbvirtual machines (primary and secondary authoritative server)

3.1 Enable the ISC BIND 9 repository for Enterprise Linux 9

- Add the ISC BIND 9 repository to the packet-manager repository list

% dnf copr enable isc/bind

- Install the EPEL (Extra Packages for Enterprise Linux) repository (required for additional dependencies needed for BIND 9.20)

% dnf install epel-release

3.2 Installing BIND 9.20

- Install BIND 9.20 from the ISC repositories

% dnf install isc-bind

- ISC and EPEL signing keys

Importing GPG key 0xC35B531D: Userid : "isc_bind (None) <isc#bind@copr.fedorahosted.org>" Fingerprint: 490C 4AE6 3D8A 6B24 A641 2C8D ED4A 0B1B C35B 531D From : https://download.copr.fedorainfracloud.org/results/isc/bind/pubkey.gpg Importing GPG key 0x3228467C: Userid : "Fedora (epel9) <epel@fedoraproject.org>" Fingerprint: FF8A D134 4597 106E CE81 3B91 8A38 72BF 3228 467C From : /etc/pki/rpm-gpg/RPM-GPG-KEY-EPEL-9

- Quick reference for the

nameddaemon:- The configuration file can be found at:

/etc/opt/isc/scls/isc-bind/named.conf - Command line options for the daemon can be specified in:

/etc/opt/isc/scls/isc-bind/sysconfig/named

- The configuration file can be found at:

- Note that due to the nature of Software Collections, no BIND 9

daemon or utility installed by these packages is available in $PATH

by default. To be able to use them, do the following:

- To enable the Software Collection for the current shell, run

scl enable isc-bind bash - To enable the Software Collection inside a shell script, add the

following line to it:

source scl_source enable isc-bind

- To enable the Software Collection for the current shell, run

% source scl_source enable isc-bind % which named /opt/isc/isc-bind/root/usr/sbin/named

- Add BIND 9 SCL path to bash shell startup

% echo "source scl_source enable isc-bind" >> .bashrc

- Link the ISC BIND configuration file directory into the

/etcdirectory (for easy access)

% ln -s /etc/opt/isc/scls/isc-bind /etc

- Enable and start BIND 9

% systemctl enable --now isc-bind-named

- Check that BIND 9 is running without errors

% rndc status % systemctl status isc-bind-named

3.2.1 A configuration file for an authoritative BIND 9 server

- Let's tweak the configuration file

/etc/isc-bind/named.conffor an authoritative-only DNS server

options {

directory "/var/named";

listen-on { any; };

listen-on-v6 { any; };

dnssec-validation no;

recursion no;

minimal-responses yes;

minimal-any yes;

querylog no;

max-udp-size 1232;

edns-udp-size 1232;

zone-statistics yes;

};

- Logging for the authoritative server

logging {

channel default_syslog {

// Send most of the named messages to syslog.

syslog local2;

severity debug;

};

channel xfer {

file "transfer.log" versions 10 size 10M;

print-time yes;

};

channel update {

file "update.log" versions 10 size 10M;

print-time yes;

};

channel named {

file "named.log" versions 10 size 20M;

print-time yes;

print-category yes;

};

channel security {

file "security.log" versions 10 size 20M;

print-time yes;

};

channel dnssec {

file "dnssec.log" versions 10 size 20M;

print-time yes;

};

channel ratelimit {

file "ratelimit.log" versions 10 size 20M;

print-time yes;

};

channel query_log {

file "query.log" versions 10 size 20M;

severity debug;

print-time yes;

};

channel query-error {

file "query-errors.log" versions 10 size 20M;

severity info;

print-time yes;

};

category default { default_syslog; named; };

category general { default_syslog; named; };

category security { security; };

category queries { query_log; };

category dnssec { dnssec; };

category edns-disabled { default_syslog; };

category config { default_syslog; named; };

category xfer-in { default_syslog; xfer; };

category xfer-out { default_syslog; xfer; };

category notify { default_syslog; xfer; };

category client { default_syslog; named; };

category network { default_syslog; named; };

category rate-limit { ratelimit; };

category update { update; };

};

- Test the configuration

% named-checkconf

- Reload the BIND 9 configuration

% rndc reconfig

- The last two commands might fail. Why? What can you do to fix the issue?

- Open port 53 (DNS) in the firewall

% firewall-cmd --permanent --zone=public --add-service=dns % firewall-cmd --reload

- Test if you can reach your new authoritative server from the DNS

resolver

- from the resolver machine (

NNN= your number)

- from the resolver machine (

$ dig @nsNNNa.dnslab.org ch TXT version.bind

3.3 Solution "Building an authoritative DNS Server":

- Issue: The

/var/nameddirectory is missing and needs to be owned by thenameduser. - Create the

/var/nameddirectory

% mkdir /var/named

- Adjust the permissions on the BIND 9 home directory

% chown named: /var/named

- The BIND 9 process should now successfully load the new configuration

% rndc reconfig

3.4 Create a primary zone

- Work on the primary DNS server

nsNNNa - Goal: a working primary zone for this training lab environment

- The trainer will publish the solution after some time into the exercise, but first try to create the configuration without outside help

3.4.1 A zone file

- Create a new zone file for the zone

zoneNNN.dnslab.orgin the BIND 9 home directory/var/named - The zone records should have a TTL of 60 seconds (not recommended for production, but required for the course labs)

- The zone should contain: 1 x SOA, 2 x NS records (for

nsNNNaandnsNNNb) - One A record for the name

primary.zoneNNN.dnslab.org(IPv4 ofnsNNNa) - One AAAA record for the name

primary.zoneNNN.dnslab.org(IPv6 ofnsNNNa) - One A record for the name

secondary.zoneNNN.dnslab.org(IPv4 ofnsNNNb) - One AAAA record for the name

secondary.zoneNNN.dnslab.org(IPv6 ofnsNNNb) - A TXT record with the owner-name of

textand a text of your choice - Two MX records for

primaryandsecondarywith different preference values - Check the syntax of your zone-file with

named-checkzone

3.4.2 Register the zone in the BIND 9 configuration

- Create a zone block in

named.conffor a primary zone for the zone created in the last chapter - Test the configuration with

named-checkconf -z - Reload the BIND 9 configuration

- Verify that

nsNNNa.dnslab.organswers authoritatively for this zone (AA-Flag!)

3.4.3 Solution for primary zone

- The Zonefile (your zone will have different IPv4 and IPv6 addresses)

$TTL 60

@ IN SOA nsNNNa.dnslab.org. hostmaster.zoneNNN.dnslab.org. 1001 1h 30m 41d 30

IN NS nsNNNa.dnslab.org.

IN NS nsNNNb.dnslab.org.

IN MX 10 primary

IN MX 20 secondary

primary IN A 192.0.2.53

IN AAAA 2001:db8:100::53

secondary IN A 192.0.2.153

IN AAAA 2001:db8:200::53

text IN TXT "DNS Leap Ahead!"

- The primary zone configuration on

nsNNNa

zone "zoneNNN.dnslab.org" {

type primary;

file "zoneNNN.dnslab.org";

};

3.5 Register the zone on a secondary server

- Work on the secondary DNS server

nsNNNb - Goal: a working secondary zone for this training course

- The trainer will publish the solution after some time into the exercise, but first try to create the configuration without outside help

- Create a zone block in

named.confon the secondary server to load the zonezoneNNN.dnslab.orgfrom the primary server via zone transfer - Check the configuration with

named-checkconf -z - Reload the BIND 9 configuration

- Check the log files for errors

- Check the file

transfer.logfor successful transfer of the zone- The transfer fails – why? How to solve this issue?

- Verify that

nsNNNb.dnslab.organswers authoritatively for this zone (AA-Flag!) - Verify the delegation of your DNS servers with

dig zoneNNN.dnslab.org +nssearch

3.5.1 Solution for secondary zone

- Starting with BIND 9.20.0, outgoing zone transfers are no longer

enabled by default. An explicit

allow-transfer ACLmust now be set at the zone, view, or options level to enable outgoing transfers.- Here we use a simple "allow all" ACL (restoring the old, pre-BIND-9.20 behavior. We will learn later in the course how to secure zone transfer with cryptographic keys (TSIG).

- The primary zone on

nsNNNa

zone "zoneNNN.dnslab.org" {

type primary;

file "zoneNNN.dnslab.org";

allow-transfer { any; };

};

- The secondary zone on

nsNNNb

zone "zoneNNN.dnslab.org" {

type secondary;

primaries { <ipv6-address-of-primary>; <ipv4-address-of-primary>; };

file "zoneNNN.dnslab.org";

};

4 BIND 9 repositories for up-to-date BIND 9 versions

5 A quick look at DNSSEC

5.1 DNS Security (or lack of)

- the classic DNS from 1983 has not been designed with security in mind

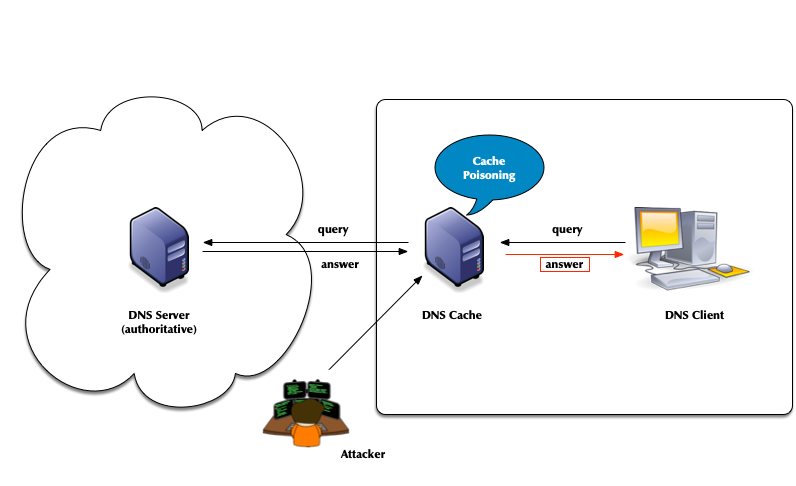

- Attack vector: DNS cache poisoning

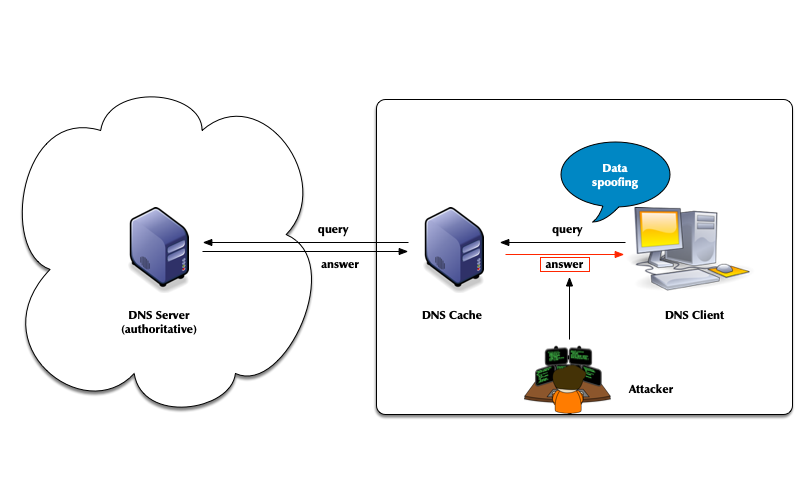

- Attack vector: Men-in-the-Middle data spoofing

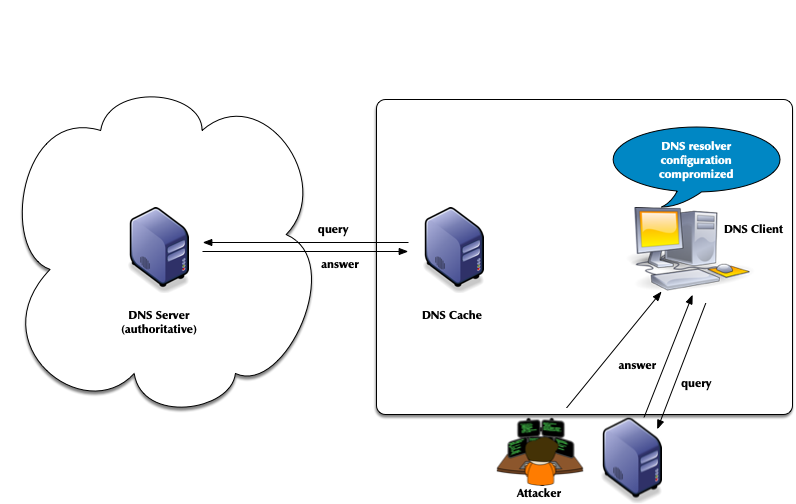

- Attack vector: changes to the client DNS resolver configuration

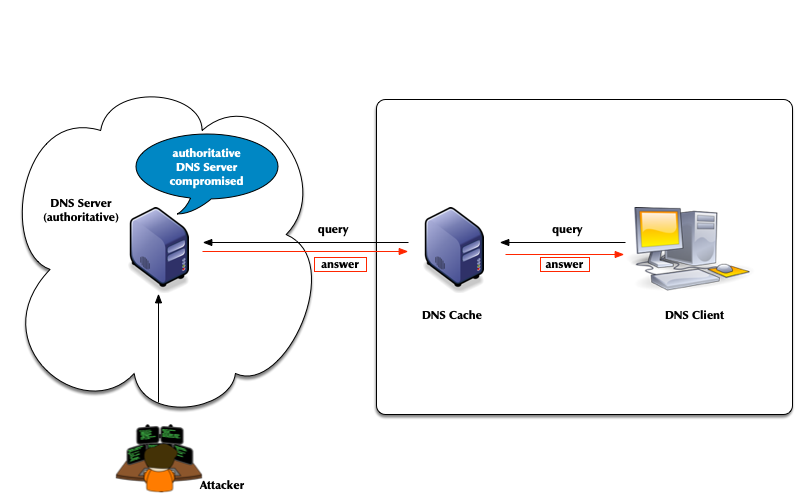

- Attacks of authoritative DNS servers

- DNSSEC can help

5.2 DNSSEC

- The DNS security extension DNSSEC secures DNS data by augmenting

the data with cryptographic signatures

- The owner (administrator) creates a pair of private and public keys for each DNS zone (asymmetric crypto)

- The owner/administrator signs all DNS data with the private/secret key

- The recipient of the data (DNS resolver or client operating

system or application) will verify (validate) the data

- That the data has not been changed on the server nor during transit

- That the data comes from the owner (the owner of the private key)

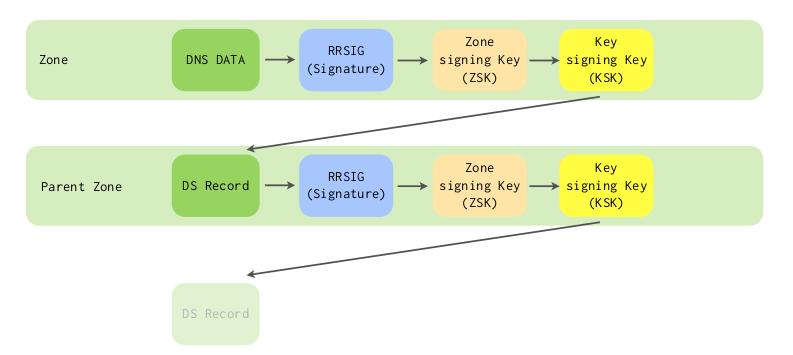

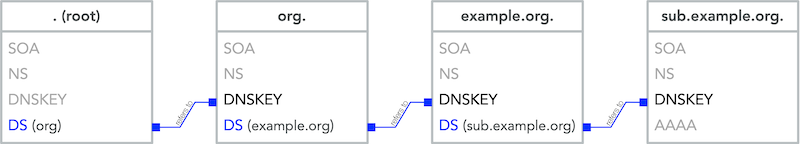

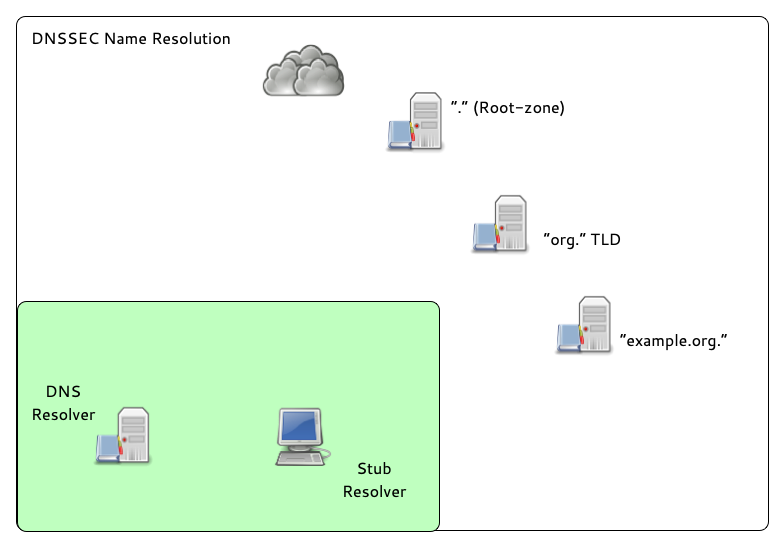

5.3 The chain of trust in DNS

- DNSSEC creates a chain of trust between the parent zone and the child zone

- Applications and DNS resolvers can follow the chain of trust to a configured trust anchor to validate the DNS data

- We will look into DNSSEC in more details later in this course

6 Cryptography in DNS (short)

6.1 Cryptography for DNS Admins

- Cryptography has four purposes:

- Confidentiality – keeping data secret

- Integrity – Is it "as sent"?

- Authentication – Did it come from the right place?

- Non-Repudiation – Don’t tell me you didn't say that.

- DNSSEC implements: Authentication & Integrity

- The IETF has added confidentiality since 2016:

- DNS uses different authenticity and integrity techniques depending on the application.

- Symmetric Cryptography

- Message Digests (aka: hashes, hash values, fingerprints)

- Message Authentication Codes

- Asymmetric Cryptography

- Digital Signatures

6.2 Symmetric Cryptography

- Symmetric cryptography provides both integrity and authenticity.

- A single key is stored and used by both (all) parties.

- The key encrypts and decrypts.

- The key is a shared secret.

- The system is known as pre-shared key (PSK).

- Securely getting the key to all parties can be a challenge.

- Symmetric cryptography requires mutual trust.

- "My security is good, but what about the other person's?"

- If all sides are administered by one party, trust is a non-issue.

- For DNS, Pre-Shared-Keys (PSK) work well:

- between primary and secondary servers (TSIG).

- for dynamic DNS updates (TSIG).

- for controlling BIND 9 with

rndc(TSIG).

- For DNS, PSKs do not work well:

- between DNS Resolver servers and authoritative DNS servers (DNSSEC).

- between stub resolver & DNS Resolver servers (DNSSEC amongst other).

6.2.1 Confidentiality: Not the Goal

- A Pre-Shared Key (PSK) could be used to encrypt a message.

- If it decrypts, confidentially, integrity, and authenticity are assured.

- However, confidentiality was not a design goal (of DNSSEC).

- Encrypting everything is computationally expensive.

- The alternative is more complicated but less expensive.

6.2.2 Message Digest

- Creating a hash of the message is a light-weight alternative to

encrypting everything.

- A hash is also known as a hash value, a message digest (MD) or a fingerprint.

- The sender runs a cryptographic hashing algorithm on the message to

produce a fixed-length hash.

- The message and hash are sent over an insecure path.

- As the sender did, the receiver hashes the message.

- If the hashes match, the message was not modified. Message integrity is proven.

- However, the receiver does not know if the message and hash were both replaced: Message authenticity is unknown.

- Confidentiality is not provided.

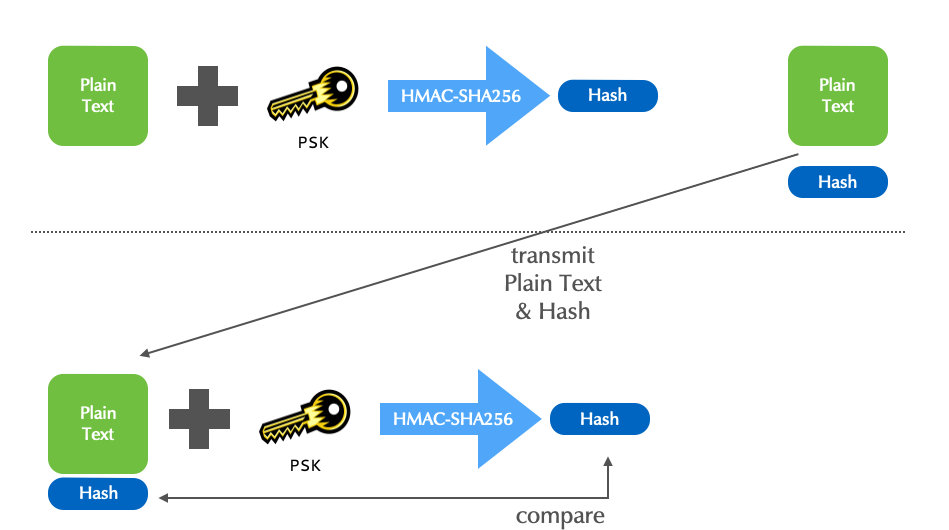

6.2.3 Message Authentication Codes

- Hashing, with a symmetric key added to the input, efficiently

provides integrity and authenticity.

- There is no confidentiality.

- A MAC is a fingerprint (MD, hash) created with the message and a PSK as input.

- The MAC described here, is a keyed HMAC (Hash-based message

authentication code).

- It is used by DNS.

- Although HMACs efficiently assure both the sender's authenticity,

and the message's integrity, not all applications can use

(pre)shared keys.

- "Am I really seeing the website

mybank.example?" - "Is the email I'm reading really from Edward Snowden?"

- "Is this RRSet actually for

theguardian.com?"

- "Am I really seeing the website

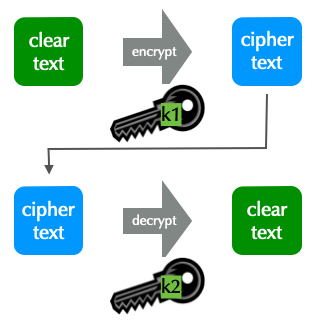

6.3 Asymmetric Cryptography

- In DNS, asymmetric cryptography is used for DNSSEC.

- This asymmetric cryptography section is a short overview.

- Asymmetric cryptography uses two keys, a pair.

- Data encrypted with one key can only be decrypted by the other.

- A key cannot decrypt what it encrypted!

- One key of a pair is declared as public, the other as private.

- The private key is highly sensitive, never shared, and must be well protected.

- The public key is made widely available without concern for who knows it.

- The technique is known as public key encryption.

6.3.1 Two Applications for public key (PK) Encryption

- PK encryption is used for privacy, to assure only the intended

receiver can read a message.

- Data integrity is also assured.

- Used in DNS-over-TLS and DNS-over-HTTPS

- PK encryption is used for authenticity, assuring the recipient,

that the message came from a specific sender.

- This is known as signing a message.

- Data integrity is also assured.

- Used in DNSSEC, as well in DNS-over-TLS and DNS-over-HTTPS

6.3.2 PK Application 2: Encryption for Authenticity

- To assure authenticity, a sender encrypts a message with her

private key.

- Anyone decrypting the message with the public key is assured it came from the holder of the private key.

- The message is encrypted, but there is no privacy.

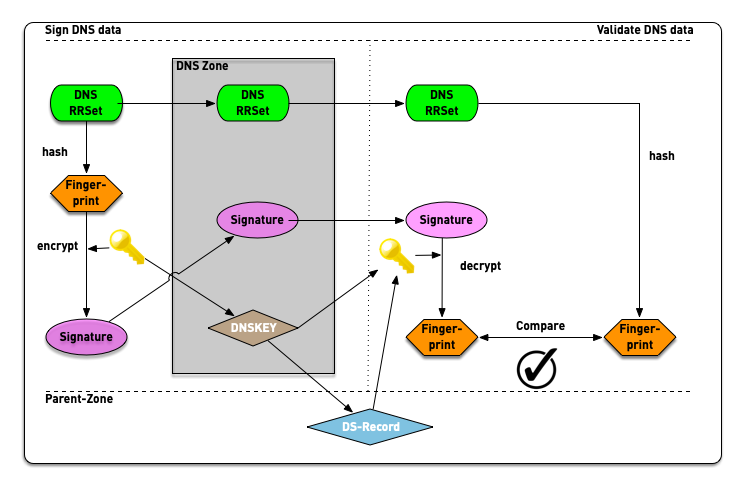

6.3.3 PK Application 2: Encryption for Authenticity: Digital Signatures

- For efficiency, the message itself is not encrypted.

- The message is first hashed to create a fingerprint.

- The fingerprint is encrypted.

- The signed fingerprint is a digital signature (aka encrypted fingerprint and encrypted hash).

A fingerprint is also known as a hash, digest, or

message digest. A signature is not the same thing.

However, the terms are often used interchangeably.

6.3.4 Digital Signatures in DNSSEC

6.4 DNSSEC

- The DNS Security Extensions, described in RFC 2065 (old DNSSEC), allow a zone administrator to digitally sign zone data

- The base DNSSEC RFCs:

- RFC 4033 to 4035 - Updates DNSSEC to DNSSECbis, published March 2005:

- RFC 4033 - DNS Security Introduction and Requirements

- RFC 4034 - Resource Records for the DNS Security Extensions

- RFC 4035 - Protocol Modifications for the DNS Security Extensions

- The DNS security extension DNSSEC secures DNS data by augmenting

the data with cryptographic signatures

- The owner (administrator) creates a pair of private and secret keys for each DNS zone (asymmetric crypto)

- The owner/administrator signs all DNS data with the private/secret key

- The recipient of the data (DNS resolver or client operating

system or application) will verify (validate) the data

- That the data has not been changed on the server nor during transit

- That the data comes from the owner (the owner of the private key)

- DNSSEC signs data to guarantee authenticity and integrity.

- It assures a client that a RRSet is from the proper authoritative sever and has not changed.

- DNSSEC does not encrypt data to provide privacy.

- Anyone can find out the RRSets you request.

- DNS Servers that support DNSSEC

- BIND 9: Authoritative server and validating resolver

- NSD from NLnet Labs: Fast authoritative server

- Unbound from NLnet Labs :Fast and secure validating resolver

- Windows DNS Server: Authoritative server and validating resolver

- PowerDNS authoritative: Authoritative DNS Server with (optional) SQL Database backend

- PowerDNS Recursor: a resolver with support for DNSSEC validation

- Knot-DNS: fast authoritative DNS Server from

nic.cz - Knot-DNS Resolver: recursive server with DNSSEC from

nic.cz

6.5 TSIG vs. DNSSEC

- TSIG uses a keyed cryptographic hash algorithm, which requires that both endpoints share a key

- DNSSEC uses public key cryptography, which doesn't require shared keys

- Zone data is signed by the zone administrator

- This provides an end-to-end integrity check between producer (DNS Administrator) and consumer (Resolver, Application)

6.6 DNSSEC:Design Choices Made

- DNSSEC signs RRSets, but alternatives were available to the designers:

- An entire DNS message could be signed.

- Just the answer section of a message could be signed.

- Each RR in an answer could be signed.

- DNS messages and answer sections are dynamically generated when a query arrives. = The signatures would have to be dynamically generated.

- RRs and RRSets aren't modified when a query arrives at an

authoritative server.

- Signatures can be created when the zone is compiled.

- Signing each RRSet is most effectively and what is done.

7 DNSSEC in a nutshell

- In DNSSEC, each zone has one or more key pairs.

- The private key of each pair

- Is stored securely (probably on a hidden primary)

- Is used to sign zone data

- Should never be stored in a RR

- The public key of each pair

- Is stored in the zone data, as a DNSKEY record

- Is used to verify zone data

- The private key of each pair

- A private key signs the hashes of each RRSet in a zone.

- The public key is accessible through a standard RR.

- Recursive servers or clients query for the public key RR in order to decrypt a hash.

- The RR is known as the DNSKEY and covered below.

7.1 DNSSEC records

7.1.1 RRSIG

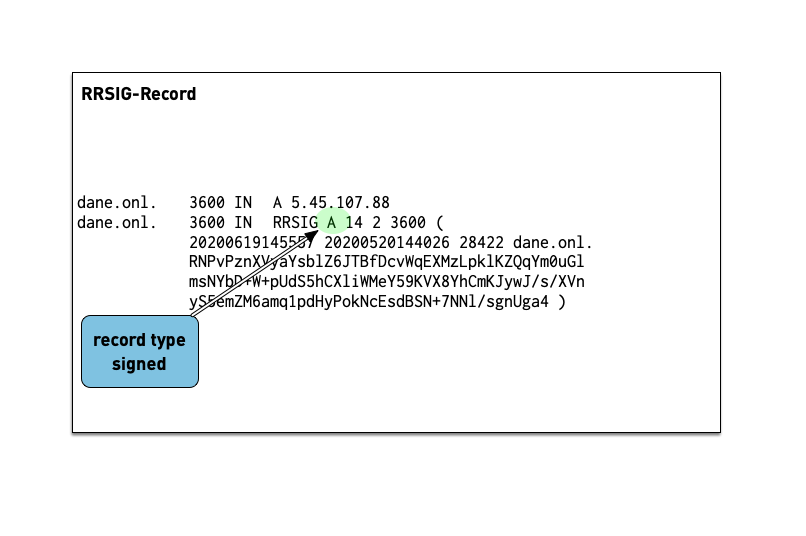

- The RRSIG records holds the cryptographic signature over the DNS data. The first field of the RRSIG holds the type this RRSIG is for. Together with the domain name of the RRSIG this data is important to match the signature to the data record.

- A zone's private key signs the RRSets in the zone.

- The signatures are added to the zone as RRSIG RRs.

- If two key pairs are in use, each RRSet is signed twice, and there is double the number of signatures.

- Signatures have start and expiration times (typically a month or

less apart).

- They must be replaced before expiring. BIND 9 can automate the signature updates.

- Keys don't have expiration timers.

- Work on the DNS resolver machine

- Ask for the DNSSEC signature of

dnssec.works NS:$ dig dnssec.works NS +dnssec +multi

- Answer these questions

- Which algorithm is this zone using? check the number against IANA Domain Name System Security (DNSSEC) Algorithm Numbers

- When does the signature expire?

- When did the signature become valid?

7.1.2 DNSKEY

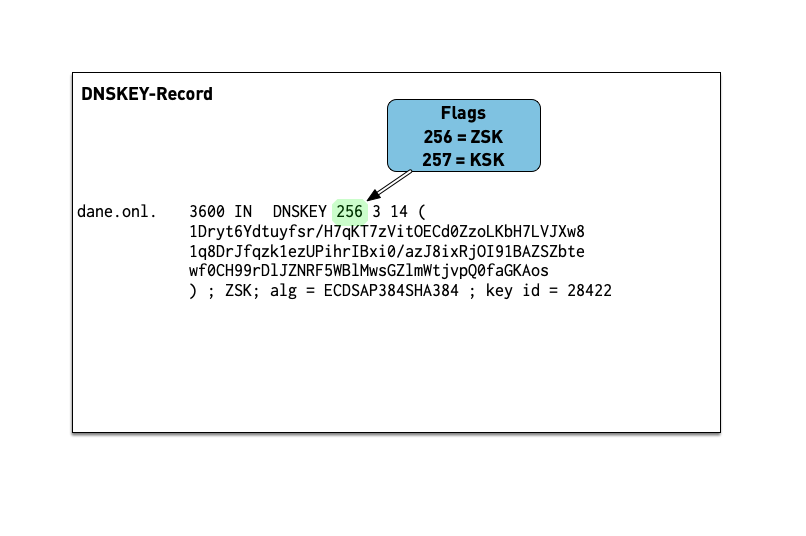

- The public key of a DNSSEC key pair is stored in an DNSKEY RR.

- The private key is not publicly available or accessible through DNS.

- DNSKEY RRs are stored in the zone they can verify.

- This conveniently means the zone administrator can sign all the RRSets and create the DNSKEY RRSet.

- Work on the DNS resolver machine

- Ask for the DNSSEC keys of

dnsworkshop.cz:$ dig dnsworkshop.cz DNSKEY +dnssec +multi

- Answer these questions

- Which algorithm is this zone using?

- Compare the size of keys and signature with the zone

dnssec.works - The sizes of both DNS answer messages as reported by

dig

7.2 The chain of trust in DNS

- If an attacker breaks into the server with the master zone file, she can change any data, including the DNSKEY RRSet.

- The DNSKEY RRSet is signed by the zone's private key!

- That signature, even when validated, proves nothing.

- It's a circular problem.

- External validation is needed, but we can't look beyond DNS.

- DNSSEC creates a chain of trust between the parent zone and the child zone

- Applications and DNS resolver can follow the chain of trust to a configured trust anchor to validate the DNS data

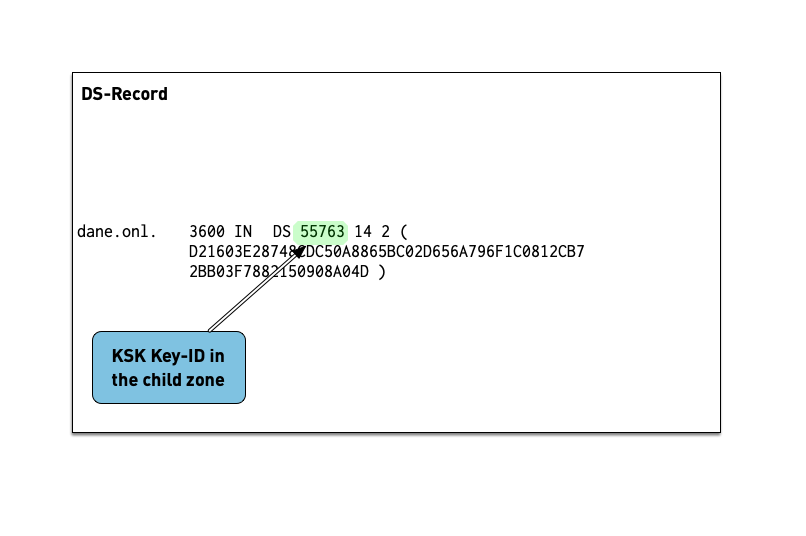

7.2.1 DS Record

- The Delegation Signer (DS) records holds the hash of the

Key-Signing-Key of a DNSSEC signed child zone.

- It is used to verify that the KSK has not been replaced without permission

- The DS record is usually submitted to the parent zone operator

via a web-based or API system implemented by the domain reseller

(registrar)

- This interface can become a target for attacker that want to change data in a DNSSEC signed zone and should be protected (two factor signon, registry lock etc).

- Work on the DNS resolver machine

- Ask for the DNSSEC delegation signer of

isc.org:$ dig isc.org DS +dnssec +multi

- Answer these questions into the chat

- Which DNSSEC-Key-Algorithm is this zone using?

- What is the current key-id of the KSK in the zone

isc.org? - What hashing algorithm is used for the DS record of

isc.orgcheck against Delegation Signer (DS) Resource Record (RR) Type Digest Algorithms?

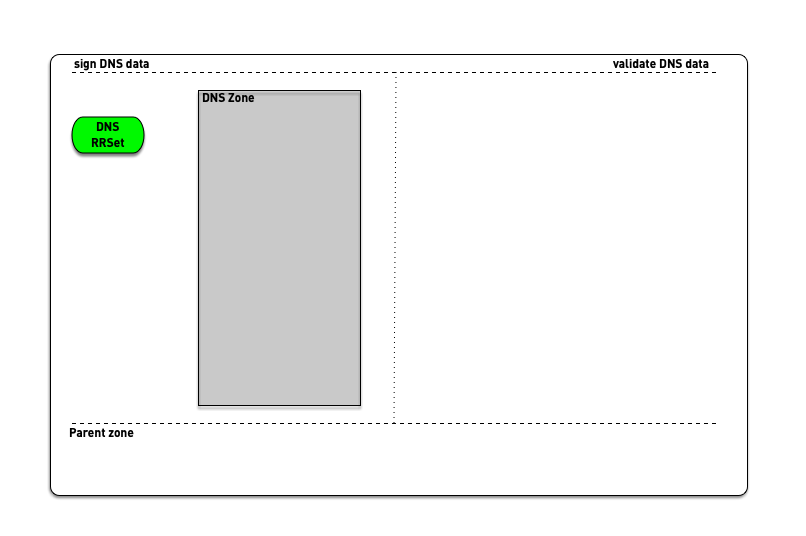

8 DNSSEC signing and validation

9 DNSSEC validation

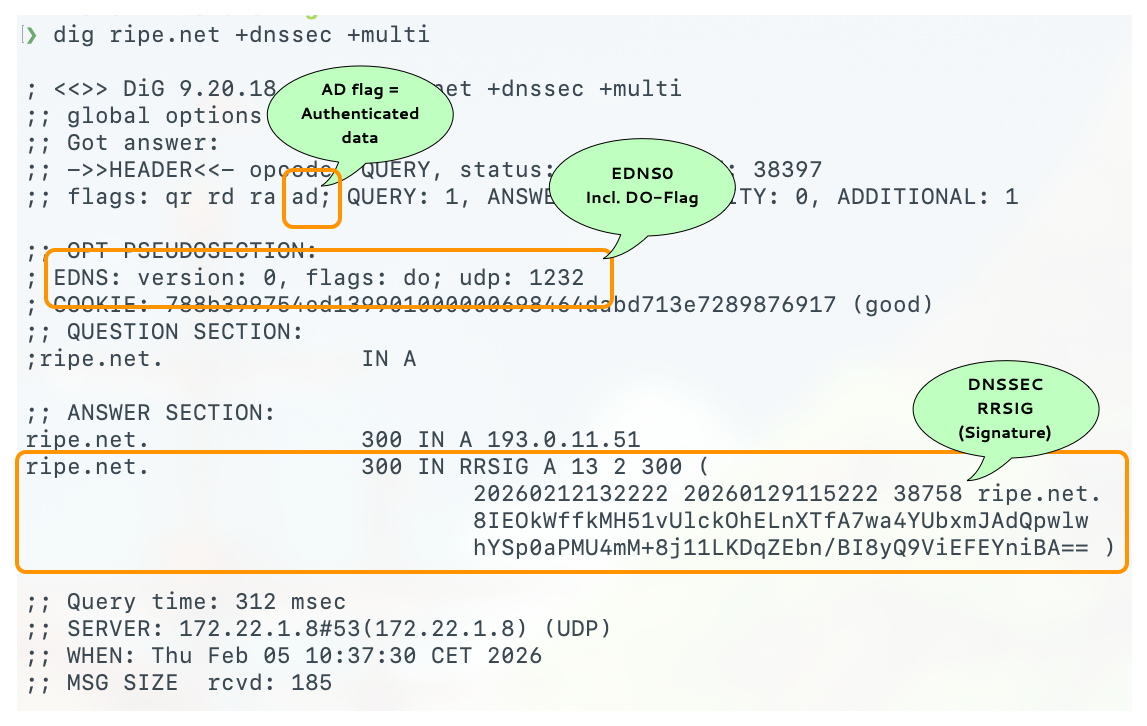

9.1 DNSSEC in DNS Messages

- Even if a client does not explicitly request DNSSEC by setting the

DOflag in a recursive query, it is protected.- It benefits from DNSSEC, if its recursive server is configured for DNSSEC.

- The recursive server will return SERVFAIL if the requested RRSet proves unauthentic.

DOFlag: DNSSEC OK- The client is requesting the authoritative server to return the

RRSIG together with the queried RRSet.

- The client is commonly a resolver, but it could be a stub resolver or application.

- With EDNS the client also announces the UDP packet size it will handle.

- If the

DOflag is not set, RRSIGs are not returned by authoritative servers.

- The client is requesting the authoritative server to return the

RRSIG together with the queried RRSet.

ADFlag: Authentic Data- The resolver uses the

ADflag to inform a DNSSEC-aware client that it has successfully authenticated the RRSet. - An unauthentic RRSet will not be sent to the client; the resolver

returns

SERVFAIL.- Without DNSSEC,

SERVFAILmeans an authoritative server isn't responding.

- Without DNSSEC,

DOis client (resolver) to authoritative server, andADis recursive resolver to client.

- The resolver uses the

CDFlag: Checking Disabled- An application or stub resolver can tell the recursive server that it will validate the DNSSEC information itself.

- This is ideal where the recursive server can't be trusted.

- A recursive server is often run by a third party, e.g. an ISP or Internet cafe, and therefore is not inherently trustworthy.

- Additionally, the connection between the application or stub resolver with even a trusted recursive server, is likely insecure.

- There is no way for a client to force a recursive resolver to use, or not use, DNSSEC.

CDwithDOtells the recursive resolver to return the queried RRSet regardless of its authentication.- The

CDflag is an excellent debugging resource. - For example, if a client receives SERVFAIL, requerying with dig can indicate if the problem is DNSSEC or not.

$ dig example.com +cdflag

- The

COFlag - Compact Answers OK- Compact Denial of Existence is a new DNSSEC extension that

allows authenticated Denial of Existence with

NSEC(and optionallyNSEC3) for online signer- it also prevents Zone Walking, even with

NSECrecords - the

COFlag is send by an DNS resolver towards authoritative DNS-servers (primary or secondary) to inform the receiver that the sender does understand the new compact answers - the

COFlag is encoded inside the EDNS-Flag-space (alongside theDO-Flag)

- it also prevents Zone Walking, even with

- Details: RFC 9824 Compact Denial of Existence in DNSSEC (September 2025)

- Compact Denial of Existence is a new DNSSEC extension that

allows authenticated Denial of Existence with

9.2 DNSSEC data in DNS messages

9.3 Basics of DNSSEC validation

- When the validator gets an RRSIG in a response, it needs the DNSKEY

and DS RR to authenticate.

- If validation fails, the signed RRs are discarded, and SERVFAIL error is returned to the client.

- If no appropriate trust anchor exists, the RRSIG is ignored.

- If the chain of trust is broken the signature is ignored.

- The steps in the following animation are simplified.

- It only shows validation using one key per zone (SSK/CSK).

- Commonly, a zone has ZSK & KSK, so there are additional steps.

9.4 Building a validating DNS Resolver

- Work on the

dnsrNNvirtual machine (DNS resolver server) - Obtain root privileges

$ sudo -s

- Install BIND 9

% dnf install bind

- Enable and start BIND 9

% systemctl enable --now named

- Check that BIND 9 is running without errors

% rndc status % systemctl status named

- Try if our BIND 9 works as a DNS resolver

$ dig @localhost switch.ch

9.5 Optimizations to the default configuration

- Work on the

dnsrNNvirtual machine (DNS resolver server) - Let's tweak the configuration file

/etc/named.conffor a resolver DNS server. Add the following new lines in theoptionsblock in the/etc/named.conffile:options { [...] dnssec-validation auto; server-id none; version none; hostname none; recursive-clients 32768; tcp-clients 1024; max-clients-per-query 1024; fetches-per-zone 2048; fetches-per-server 4096; edns-udp-size 1232; max-udp-size 1232; minimal-responses yes; querylog no; max-cache-size 2147483648; }; - The values above are for an ISP level DNS resolver. They should work for a broad range of DNS resolver machines, from small to very large.

- The new configuration statements:

dnssec-validation auto;enables DNSSEC validation via the built in trust anchor for the Internet Root-Zone. If DNSSEC is used in an closed private DNS system (not connected to the Internet), dedicated DNSSEC trust anchor must be configured.- server-id none: disable returning the server's hostname on the

query

dig @ip-of-server ch TXT hostname.bind - version none: disable returning the BIND 9 version number on

the query

dig @ip-of-server ch TXT version.bind - recursive-clients: number of concurrent DNS queries over UDP that are allowed from clients

- tcp-clients: number of concurrent DNS queries over TCP that are allowed from clients

- max-clients-per-query 1024: rate-limiting - number of concurrent clients that can request the same query

- fetches-per-zone: rate-limiting - maximum number of concurrent DNS queries inside one zone

- fetches-per-server: rate-limiting - maximum number of concurrent DNS queries towards one authoritative DNS server

- edns-udp-size: maximum UDP answer size requested from authoritative servers

- max-udp-size: maximum UDP answer size when sending answers to clients

- minimal-responses yes: only fill the authority and additional sections when necessary by the DNS protocol

- querylog no: disable query logging on start/restart even if configured. Query logging slows down the DNS resolver

- max-cache-size 2147483648: use a maximum of 2GB for the DNS cache. A larger cache often has a negative impact on the DNS resolvers performance. If unsure, test with a performance benchmark.

- Check the configuration with

named-checkconfand reload the BIND 9 configuration withrndc reconfig - Make sure that the DNS resolver still does resolve DNS names in the Internet

9.6 Extended DNS errors (EDE)

- RFC 8914 - Extended DNS Errors defines a way to deliver additional

error information in an DNS response. It is implemented in

digsince version BIND 9.16.4. BIND 9.18 and other open source DNS-Server support EDE-Messages, as well as some DNS resolver on the Internet (like Cloudflare):

$ dig lame.defaultroutes.org soa @1.1.1.1 < ; <<>> DiG 9.18.41 <<>> lame.defaultroutes.org soa @1.1.1.1 ;; global options: +cmd ;; Got answer: ;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: SERVFAIL, id: 29410 ;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 0, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1 ;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION: ; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 1232 ; EDE: 22 (No Reachable Authority): (at delegation lame.defaultroutes.org.) ;; QUESTION SECTION: ;lame.defaultroutes.org. IN SOA ;; Query time: 705 msec ;; SERVER: 1.1.1.1#53(1.1.1.1) (UDP) ;; WHEN: Mon Nov 03 13:19:33 CET 2025 ;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 94

9.7 DNS/DNSSEC error reporting

- The RFC 9567 - DNS Error Reporting describes a way for DNS resolver software to report DNS name resolution error conditions back to the operator of the authoritative DNS zone

- This function is similar to DMARC reporting in email

- The errors reported are based on "Extended DNS Errors (EDE, RFC 8914)"

- The reporting is done within the DNS protocol

- Authoritative DNS server can opt-in for error reports using an EDNS option

- Authoritative DNS Server can select to receive only error conditions or also positive feedback (on successful name resolution)

- To report an error, the reporting resolver encodes the error

report in the QNAME of the reporting query. The reporting

resolver builds this QNAME by concatenating the

_erlabel, the extended error code, the QTYPE and the QNAME that resulted in failure, the label_eragain, and the reporting agent domain - The resulting domain name (QNAME) is then used to query for a NULL resource record, which will report back the error condition

- The reporting agent domain is usually different from a production domain. The reporting agent domain should not be DNSSEC signed, as only the queries are of use and the responses do not need to be secured

- The authoritative DNS server will respond with a NODATA/NXRRSET response, which will be cached by the resolver (the negative TTL on this response will set the error report interval, as new reports for the same error will only be send once the TTL has expired)

- Example (taken from the RFC):

- The domain

broken.testis hosted on a set of authoritative servers. One of these serves a stale version. This authoritative server has a severity level of 1 and a reporting agent configured:a01.reporting-agent.example. - The reporting resolver is unable to validate the

broken.testRRSet for type A, due to an RRSIG record with an expired signature. - The reporting resolver constructs the QNAME

_er.7.1.broken.test._er.a01.reporting-agent.exampleand resolves it. This QNAME indicates extended DNS error 7 occurred while trying to validatebroken.testtype 1 (A) record. - After this query is received at one of the authoritative servers

for the reporting agent domain (

a01.reporting-agent.example), the reporting agent (the operators of the authoritative server fora01.reporting-agent.example) determines that the authoritative server for thebroken.testzone suffers from an expired signature record (extended error 7) for type A for the domain namebroken.test. The reporting agent can contact the operators of broken.test to fix the issue.

- Error Reporting is currently available in Unbound (Version 1.23 - April 2025) and will be available in the upcoming BIND 9.22.x versions (Q1/Q2 2026).

- The domain